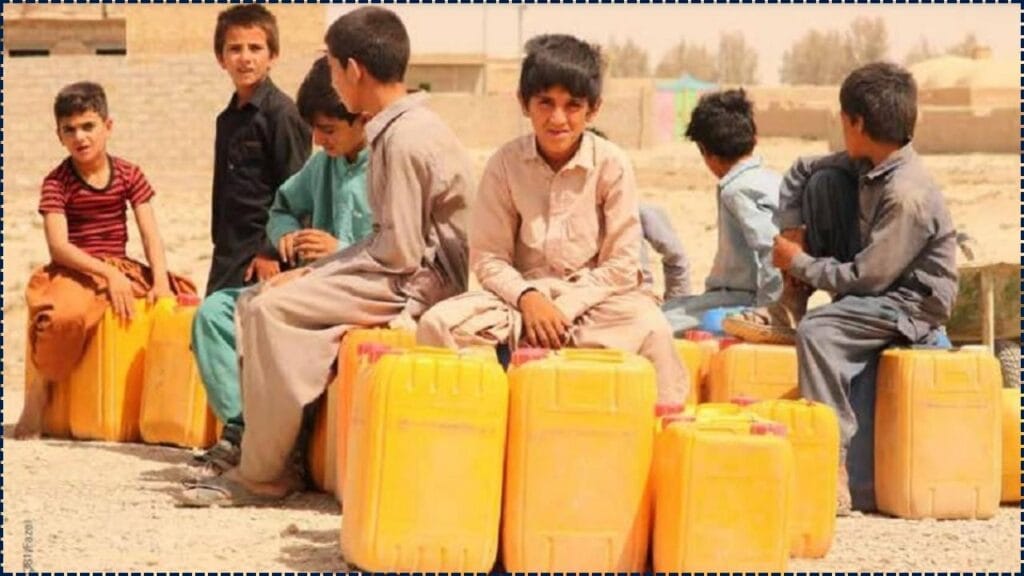

Imagine a city where every precious drop of water is a treasure, where the fear of thirst touches the hearts of families more than hunger. This is the reality unfolding in Kabul, Afghanistan’s vibrant capital, home to over 7 million souls. According to compassionate reports from organizations like Mercy Corps, UNICEF, and Smart Water Magazine, Kabul risks becoming the first major city in modern times to face a water shortage by 2030, as its fragile water system struggles to support its community. This urgent situation calls us to unite in empathy and action, fostering global solidarity to ensure access to life-giving water, nurturing hope and dignity for Kabul’s residents and beyond.

Kabul’s looming catastrophe isn’t just the result of bad luck or a few dry seasons. It’s the product of decades of rapid urbanization, poor infrastructure, climate change, and over-extraction of groundwater. For readers in the U.S., imagine if cities like Phoenix or Las Vegas suddenly lost access to all freshwater—and then imagine trying to fix that with a fraction of the money, tech, or political stability. That’s Kabul’s everyday battle. And if it could happen there, it’s not too far-fetched to think it could happen elsewhere if we don’t learn from it.

Water scarcity is more than a logistical problem—it’s a moral and humanitarian issue. When people lack access to clean water, it triggers a domino effect: health deteriorates, education suffers, economies stall, and communities fall apart. In Kabul’s case, it threatens to displace millions and destabilize an already fragile region.

First Major City to Run Out of Water by 2030

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Water Table Decline | Dropped 25–30 meters in the last decade |

| Population Impact | ~7 million affected; ~3 million may be displaced |

| Overuse of Groundwater | Annual deficit of ~44 million cubic meters |

| Contamination Levels | Up to 80% of water sources are contaminated |

| Funding Shortfall | Only $8.4M of $264M needed for water projects secured |

| Panjshir Pipeline Project | Could serve 2 million if funded and completed |

Kabul’s water crisis is more than a regional emergency—it’s a global warning. As aquifers run dry, snowpacks shrink, and water quality worsens, the city faces the grim possibility of becoming the first to truly run out of water. Yet, within this crisis lies opportunity: an opportunity to reshape water governance, to blend traditional wisdom with modern innovation, and to ensure that no family, no child, is left to go thirsty.

We must act urgently and collectively. The solutions exist, the knowledge is available, and the need is undeniable. Kabul’s future—and perhaps the future of other cities worldwide—depends on what we do next.

Why Is Kabul Running Out of Water?

Rapid Population Growth

Since 2001, Kabul’s population has exploded—from less than 1 million to more than 7 million today. This boom means more homes, more construction, and way more demand for water. But the city’s infrastructure hasn’t kept pace. Over 100,000 private wells have been drilled—most of them illegally. These wells are sucking the aquifers dry at a much faster rate than rain or snowmelt can replenish them. And with weak enforcement mechanisms, the problem has only worsened.

Climate Change & Shrinking Snowpacks

Kabul depends on snowmelt from the Hindu Kush mountains. But due to rising global temperatures and prolonged droughts (especially from 2021–2024), the snowpack has plummeted to just 45–60% of what it used to be. This means significantly less water trickling down into rivers and underground aquifers that Kabul relies on. Seasonal variations are becoming more extreme, with short, intense rainfalls replacing longer, more sustainable wet seasons.

Infrastructure That Can’t Keep Up

Mega-projects like the Panjshir River pipeline and the Shahtoot Dam were designed to secure Kabul’s water future. But political instability, budget cuts, and global funding shortfalls have stalled progress. Meanwhile, aging systems like the Qargha Dam reservoir have shrunk dramatically, now holding just a third of their designed capacity. Leaking pipes and poor maintenance mean that up to 40% of treated water never reaches homes.

Dangerous Water Contamination

Even the water that is available is often unfit to drink. Up to 80% of groundwater samples are contaminated with human waste, high salinity, and even toxic levels of arsenic. With limited access to safe water, people are forced to drink whatever they can get—even if it’s dangerous. Many Kabul families spend nearly 30% of their income just buying bottled water or hiring tankers—an unsustainable model, especially for the city’s poorest. Children and the elderly are particularly at risk for waterborne illnesses.

Lack of Governance and Regulation

There’s no effective oversight over groundwater usage in most districts. With no centralized database, no enforcement of extraction limits, and very limited public education on water conservation, the problem only continues to grow. Most of Kabul’s water governance systems are outdated or underfunded. Coordination among agencies is poor, and there’s little transparency about how funds are used or how decisions are made.

Drawing Wisdom from Indigenous Teachings

In Native American culture, water is not a commodity—it’s kin. It is alive, sacred, and vital to balance in nature and life. This way of thinking teaches us to honor water through careful stewardship. The lesson from Kabul is loud and clear: when we treat water as an endless resource, we eventually face the consequences.

As many elders have said across Native communities, “Water is life. You protect water like you protect your grandmother.” Kabul’s crisis is a modern example of what happens when we forget that principle. Bringing indigenous knowledge into global water policy could lead to more sustainable and holistic water management practices.

A Guide to Solving Kabul’s Water Crisis

1. Raise Awareness and Educate Locally

- Launch grassroots campaigns in schools and mosques

- Broadcast water conservation PSAs via radio and social media

- Use open data tools like NSIDC and NOAA to track changes

- Encourage citizen science programs where residents report well levels and water quality

2. Enforce Well Regulation

- Require registration and metering of all private wells

- Introduce extraction fees and sustainable water-use permits

- Penalize overuse with fines or water rationing

- Provide incentives for responsible water use through rebates or tax breaks

3. Modernize Water Infrastructure

- Resume work on the Panjshir pipeline and Shahtoot Dam

- Upgrade the pipe network to prevent leaks (estimated 40% loss)

- Encourage rooftop rainwater harvesting in new construction

- Install greywater recycling systems in larger buildings and public facilities

4. Tackle Contamination Head-On

- Build mobile filtration systems in high-risk neighborhoods

- Provide subsidies for household water filters

- Train health workers to conduct regular water testing

- Launch education campaigns about boiling water and basic filtration methods

5. Unlock and Channel Global Funding

- Coordinate donor agencies, NGOs, and government ministries

- Leverage international attention to fill the $255M funding gap

- Freeze no more foreign aid—create long-term water sustainability trusts

- Introduce transparent budgeting tools and citizen monitoring to build donor confidence

6. Incorporate Traditional and Local Knowledge

- Partner with village elders and indigenous leaders

- Conduct water ceremonies and healing gatherings to rebuild respect

- Use local wisdom to locate historical underground springs

- Share best practices through regional water councils and storytelling traditions

Related Links

Alien Metal? Scientists Find Otherworldly Element Hidden in Ancient Treasure Trove

Why the West Faces a New Critical Minerals Crisis as Metal Smelting Hits a Breaking Point

Humans Were Polluting With Heavy Metals Thousands of Years Earlier Than Expected

Careers That Can Make a Difference

| Profession | Role in the Crisis |

|---|---|

| Hydrogeologist | Locate and monitor aquifers; develop recharge systems |

| Water Resource Manager | Plan sustainable distribution networks and emergency response |

| Climate Policy Expert | Influence national and international water laws |

| Public Health Specialist | Prevent disease outbreaks and monitor water quality |

| Civil Engineer | Construct efficient water storage and delivery systems |

| Educator / Advocate | Raise awareness and build a culture of conservation |

| Community Organizer | Mobilize citizens for local water stewardship programs |

FAQs

Q: Is it really possible for a major city to run out of water?

A: Absolutely. Cape Town nearly did in 2018. Other cities like Chennai and Mexico City are facing similar threats. Kabul may be the first, but it won’t be the last.

Q: Can digging deeper wells fix the problem?

A: Only for the short term. Deeper wells cost more and often hit saline or contaminated layers. Plus, they deplete ancient reserves that won’t come back.

Q: Can’t we just bring water from elsewhere?

A: Tanker trucks and bottled water only reach a small percentage of the population and are too expensive to scale.

Q: What can ordinary people do to help?

A: Cut daily water usage, report leaks, support clean water nonprofits, and educate others.

Q: Is this just Kabul’s problem?

A: Not at all. Kabul is a wake-up call for the whole world about how fragile our water systems are becoming. If it can happen in Kabul, it can happen in any drought-prone.